Pennsylvania Real-Time News

As warehouses replaced farms, 1800s cemetery decayed — until luck and scouts stepped in

Updated Jan 05, 2019; Posted Apr 20, 2017

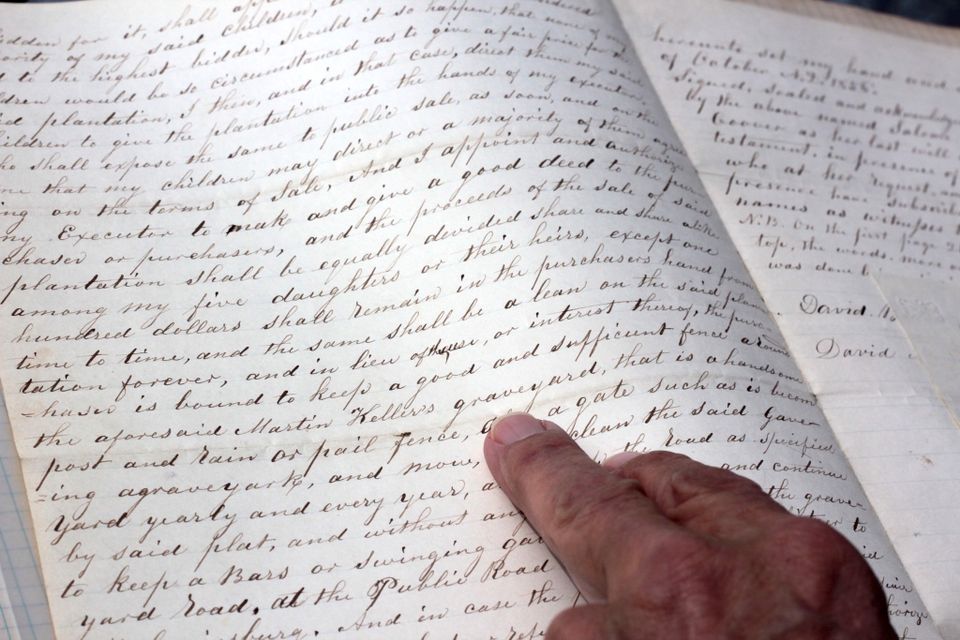

In her will, Salome Coover left specific instructions for her survivors. In formal yet flowing script, she provided not only for their comfort and care, but also for that of the graveyard that was part of the family’s farm on the outskirts of Mechanicsburg.

Salome declared that the grass was to be kept trim. The stone wall, which separated the graves from the farm’s broad fields, was to be kept in good repair. The iron gate was to be maintained in order to swing properly.

Before she died in 1883, Salome was the matriarch of a dying branch of the Coover surname. The son of her and her husband John, had died when he was an infant (his name was Amos). Their daughters had married into other families whose names are prominent to this day in the area — Longs and Hummels, Kauffmans and Zugs. Like an old oak tree, the Coover family had branched, split off and branched again. Now, this branch of the surname’s broad tree was ending. Fate and time, ever the dutiful arborists, were pruning it back.

For many, our family histories are like long anchor chains that tie us to the past. When we are children, they are the stories our parents and grandparents tell each other at the picnic table during family gatherings while we play in the grass at their feet — largely oblivious, living only in the present.

Much of a child’s early life is defined by the now, their identity drawn and created by the stories they and their parents tell and create in the immediate future and past. It isn’t until we become older, and, perhaps, aware of our own mortality that we began to explore our families’ deeper stories. They add context to our lives, part and parcel of the stories of who we are — the bedrock of what it means to carry our own surnames.

The graves of Salome’s predecessors — of all of our predecessors — are more than granite monuments in a field, or the markers of a single life. They are chapters in the broader stories of who we are, markers of the paths that our families trod that lead to who we are today.

In a field outside of Mechanicsburg, Salome Coover laid the foundation of her family’s story. There it would remain as time flowed slowly past. Over the years the fields were bought and sold, the farm passing out of the hands of her children and their children’s children. It was subdivided and parceled out as Mechanicsburg grew from a way station on the road between Carlisle and Harrisburg to the town it is today.

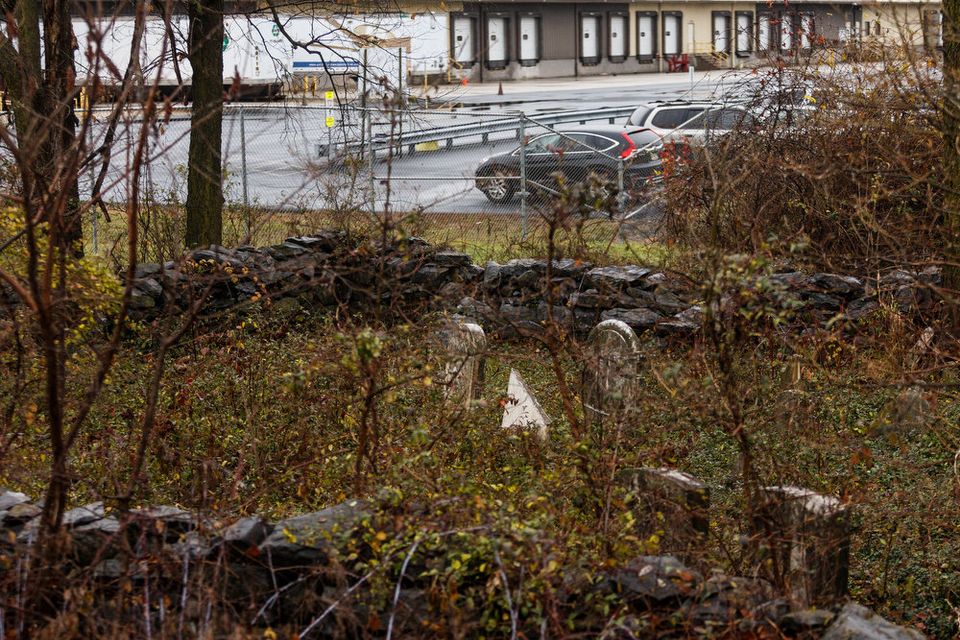

The fields, which once grew the harvest that fed her family, yielded new crops of factories and logistic centers, even as the family’s farmhouse gave way to modern houses and townhouses.

But in the shadow of a stand of trees, the family cemetery would survive, at times forgotten only to be rediscovered by a new generation of Salome and John’s descendants. Salome’s will — that the cemetery be maintained and kept in good order — would languish over the years. When one family’s branch has withered, has been intertwined with other trees, who then, other than fate and time, will tend to the trimming?

It was a bitterly cold morning in March — made even colder by the warm winter that preceded it — that Sam Colosimo had chosen to tend to Salome’s family cemetery. The weather was largely a fluke — the week before temperatures ranged near 70 degrees. The next weekend there would be more than a foot of snow covering the graves.

Colosimo took the cold weather in stride as he moved through the graveyard. In a way the cold was a blessing — he and the other Boy Scouts from Troop 180 had to keep moving to keep warm. He was here to work on his Eagle project, the highest award bestowed by the Boy Scouts of America. But it was the history of the family and the cemetery that had captured his attention.

Colosimo first encountered the Coover cemetery through a local historical society. Inquiring about a possible service project, the society put him into contact with Peter Kauffman, who, serendipitously, had been in need of an Eagle Scout. Kauffman, a descendent of the Coovers who resides in Virginia, has spent two decades researching — and searching for — the Coover Cemetery.

“His passion was inspiring,” Colosimo said. “At first I thought [this project] was going to be a handful, impossible.”

It had been six or seven years since the last time a Boy Scout had tackled the Coover Cemetery, and the graveyard was overgrown. Some of the graves had been toppled, while others stuck out of the ground like broken teeth. The stone wall that had once delineated the cemetery from the surrounding fields was in disrepair.

But between Colosimo’s scouts and volunteers from the nearby Exel warehouse, the brush which had overgrown the graves was trimmed back, and sunlight once again shone on the final resting places of Salome and her family. Each grave, all dating from the mid- to late-1800s and well worn by time and the elements, was marked off by the scouts, then surrounded by white stones and garden fabric to keep future weeds away.

Colosimo and his fellow scouts rebuilt the stone wall as best they could, moving the tumbled down stones back into a semblance of order. The iron gate that Salome mentioned in her will is long gone. But she should rest easy with the knowledge that someone — other than fate and time — is tending to her final wishes.

The snow has melted.

In the grove that contains the Coover Cemetery, a small herd of deer stand motionless, their alert ears raised almost in greeting to the visitors who have come to the now clean and quiet cemetery. The moment stretches for a long heartbeat before the deer bound off, headed deeper into the nearby industrialized landscape.

In the distance is the subdued yet persistent beep-beep-beep of a tractor-trailer at the nearby Purina plant. In the trees overhead, birds twitter back and forth as the trees’ trunks cast long shadows over the graveyard.

Kauffman walks through the yard from grave to grave, retelling the family’s story. Here are John and Salome, whose will put into motion the long litany of events that led to this morning. Here is their son, Amos, who died as an infant. And here are the Kellers, the Hows, the Kinseys and the Neiswangers, who lived and laughed and died between the late 1700s and the mid-1800s on this corner of God’s green Earth.

The cemetery contains the individual stories of more than 40 people, but also pieces of the larger story of the Coover family and, really, this corner of Mechanicsburg. From Coover to Hummel to Kohler to the Capital Region Economic Development Corp. and thence to Purina, Exel and others– the foundation for the hundreds of people who have lived and worked and died on what was once a simple family farm.

For Kauffman this spring has marked another step in a 20-year journey, retracing the steps of his family’s past and his own childhood, a journey which began with a letter from a now deceased cousin.

“Harriet Armstrong was the granddaughter of one of the Coover sisters and she’s the one who got me here,” he said. “She sent me a letter, probably 20 years ago and said, ‘I can’t find the cemetery.'”

Kauffman remembered visiting the cemetery as a child — his grandparents lived in Mechanicsburg and his family would visit them from Erie. He also inherited photographs that showed the cemetery at various stages over the last century.

So, sparked by his cousin’s letter, one weekend Kauffman packed his memories into his car and headed north.

“I knew it was in Mechanicsburg, and I knew I had relatives in Mechanicsburg, but I knew nothing about it,” he recalls. “I literally knocked on doors in downtown Mechanicsburg … until someone opened the door and showed me a book of old homes. … It kind of rekindled my interest in the area. I felt like I was rediscovering my roots, but they had been here all along.”

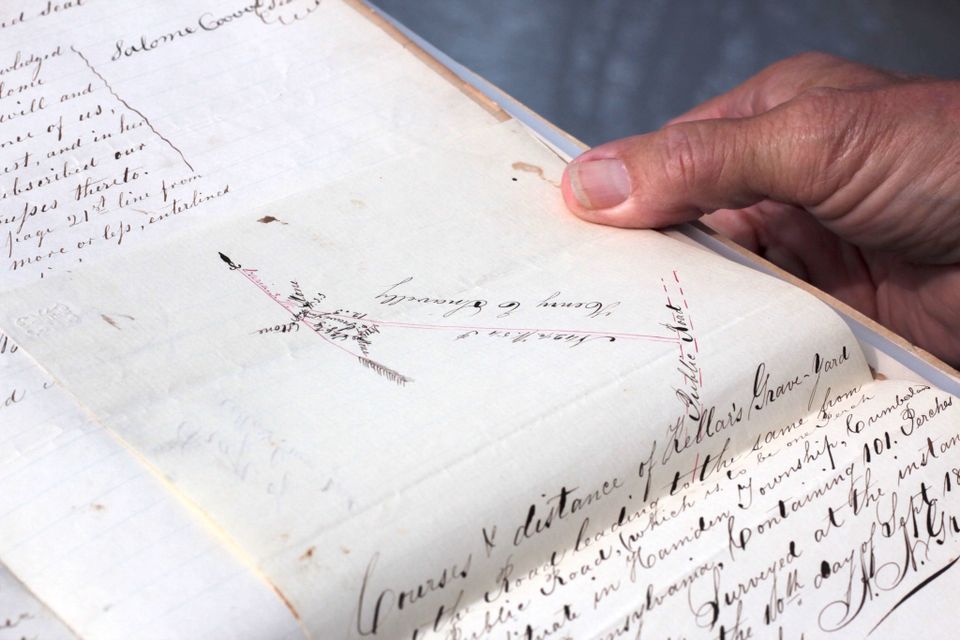

From there Kauffman researched old land deeds and property records, trying to trace the ownership of the property through the years. He found the cemetery listed as part of the original deed, which over the years had been sold and parceled off — except for the cemetery’s plot.

Kauffman said subsequent deeds mentioned the plot less and less often, until they mentioned it not at all. For his part, Kauffman firmly believes the plot’s ownership was transferred to the Capital Region Economic Development Corp. (CREDC), when it took title to the farmland in order to develop the Purina plant. For its part, CREDC said it is more than willing to sign over its interest to the plot — although the organization maintains it does not own the cemetery.

(In another wrinkle, Cumberland County property maps don’t show the cemetery as a separate plot at all, but rather run the boundary between the Purina plant and the nearby Exel warehouse properties through the middle of the cemetery.)

Moving forward, Kauffman is hoping that he can establish some form of trust that can take ownership of the land and provide for the cemetery’s maintenance. If not, he laughed, there’s always his grandson, now 10.

“Maybe I can dump all this stuff on him,” he said with a chuckle as he looked around the cemetery. “Gotta find somebody. Somebody’s got to do this. … The plight of a lot of these old cemeteries is the same. There’s not enough Boy Scout projects going.”

The future of the Coover Cemetery — even if unsettled — is still a better future than that faced by many of the small, almost forgotten cemeteries that dot our towns and villages and rural areas: Who, if not the families or volunteers, will tend to the graves? Who will tell the stories? Who will keep the family histories alive?

Or like all of us — like those whose lives the stones mark — are the cemeteries themselves destined to die? To be ground down over the centuries to dust, the stories they tell forgotten in the weed-choked brambles of history?

Who, other than fate and time, will tend to the graveyards of the past?

Just discovered your site while working on Hoch Zug and all.

Thank you for a wonderful set of photos with the history. I must visit it soon.

Nice to meet you.